Decorative Arts

|

AmeriCeltic promotes Celtic Decorative Arts. |

Support our work! |

Click Here to subscribe to our weekly Email Newsletter, and get updates every Friday. |

Table of Contents

2021-12-31 Celtic Decorative Arts Part 1 – by Celia Fábos-Becker

2022-01-07 Celtic Decorative Arts Part 2 – by Celia Fábos-Becker

2022-01-14 Celtic Decorative Arts Part 3 – by Celia Fábos-Becker

This is the first of an occasional series to remind people that the Celts were and are more than fighting clans, whisky/whiskey, music and ancient gold jewelry like torcs. In contrast, it was largely Celtic Americans and Central European Americans who created and operated the first and most prosperous industries in the U.S. between 1840 and 1990. Much more than railroads, and steel, which had significant government subsidies – those heavy industries, and their workers, did not prosper until unions both formed and were respected by government as well as corporate executives. Instead, most of America’s GDP and revenues from the goods created and produced by small industries, and were used by American homes and families. Early on, these small industries, and their workers, formed unions and guilds, many of whom were very skilled and educated, earned better incomes and respect, and kept the kinds of homes where their own products could be bought and used.

The biggest of these industries were what are now called home goods or decorative arts. Everyone had homes and families. Everyone had family events, parties with friends and the states and nations had holidays that were celebrated with decorations, parties and feasts. Everyone for a long time wanted to both ‘put their best foot forward’ and show their prosperity–and celebrate their families and friends with some of that show and prosperity, to make them feel appreciated and special also, treat them like noble guests of old.

When I was four years old, I threw the only temper tantrum my mother could ever remember me having. She had taken me to the Toledo Art Institute, and I discovered all the galleries of glass. I never wanted to leave. I was fascinated with the shapes, the uses, the colors, the many patterns and how they were made, the fine facet work on some and how the light danced off it all and filled the rooms with rainbows, shimmer and sparkle. It was like seeing jewelry magnified many times. I wanted to learn as much as I could about all of this magical, wondrous stuff. It was closing time and I had probably several dozen more questions and I had not seen and studied more than a small part of all the wonders before me. I did not want to leave and I did not want the museum to close. I clung to a leg of a large heavy case and had to be pried loose by a museum guard and my mother who had to promise me repeatedly I could return and would return soon.

I learned afterward of the great Central European and Italian traditions of glass making through my father’s family who even in the 1950’s had relatives who worked for companies like Imperial Glass, Libbey (the tableware division of Libbey Owens Ford, etc.) and several smaller companies. My grandparents and aunts had wonderful continental European porcelains and a mix of European and U.S. glassware. Interestingly, all the silverware, however, was U.S. made, everything from Oneida to Kirk and Wallace.

My late mostly Scottish and Scots-Irish mother, whose maiden surname was Wallace, was a modern Hollywood and Los Angeles girl. She considered most of the ornate older designs of porcelain, glass and silver too fussy and too much trouble to keep clean and shiny. Her tastes ran to quite different, and plainer things, except for her interest in Asian art that had begun with her experiences in the U.S. Navy in the Pacific ‘Theatre’ of World War II. She had been in Hawaii, China and Okinawa. However, my late mother knew very little of her own family history, much less the general history of Scots, Scots Irish, Irish and their influence on some of the largest and most complex and profitable industries in the U.S. I ended up learning more about that after I became an adult and starting my own home.

by Imperial Glass

Hollow Candy Holder

One of my aunts had developed an interest in Heisey Glass, and another had discovered Viking (originally Dalzell/Dazell-Viking) and Fenton glass. A cousin and I had a common interest in some of Imperial Glass’s iridized articles, especially those in the less common colors of pink, aqua blue and light green and white, and then the very interesting ‘slag’ glass that could be and was made into objects resembling sculptures made of ‘gemstones’ that were once popular in noble and royal European courts. My father had a niece, a daughter of his much older brother, whose husband worked for Imperial Glass, and my father himself had been part of a select crew of electricians who did the electrical work on the new additions and the remodeling of the Imperial Glass factories in 1954 and 1955 and then did work on the Libbey factories, both for tableware and automobile glass. However, Toledo in those days, was heavily Central and East European American and I knew nothing of the much earlier history and development of this industry and how many Scots and irish were initially involved. I would not learn that until I began acquiring a few McKee Glass, Dugan (originally spelled Doogan before the family moved to England from Ireland) Glass and Bryce-Higbee Glass items, and became curious about the history of these companies and the glass industry in the U.S..

What I found was a long, almost 400 year old history that started with Jamestown trying to find something to make to pay back English and Scottish noble investors in that colony, and keep the native Americans happier. However the investors initially laughed at the amateur efforts of the surviving 1607-8 colonists. The new managers of the colony saw potential and then brought in about a dozen Polish and Dutch glassmakers. This was more successful, but the English gentlemen and adventurers were lousy managers and abusive to those they considered beneath them. According to surviving records of the early Jamestown colonies, eight of the Dutch glassmakers eventually had enough of English management and abuse, packed up and literally moved to live among Powhatan’s people–the natives. In the two early efforts of the natives to rid themselves of the English generally, the last being in 1621-22 one group they were willing to spare, consistently, as they massacred over one third of the European settlers, was the glassmakers. They made not only bottles for spirits, and roundels for windows, for European settlers,, but more importantly, glass beads which became used for decoration and wampum–for communication and a form of currency for the natives. During the 1994-97 excavations at Jamestown a cache of beads was found that showed many beads were made in shades of blue: ‘robin’s egg,’ ‘turquoise blue’ and a dark, navy blue. They were similar to caches of 16th century Spanish trade beads, called ‘Nueva Cadiz’ suggesting the glass makers at Jamestown had learned to copy what the Spanish already found to be popular for Mexican and central American natives. Blue, as a color, has long had sacred meanings to many North and Central American native peoples. The glass makers were hard working people, and having come from middle class families and guilds, not the feudal military and social elites of the gentlemen and adventurers, they were apparently more egalitarian.

The next recorded effort was in New England, in Salem and later Boston. By 1639 the English and Scottish colonists in Massachusetts were already fed up with the unequal balance of trade between them and ‘the mother country.’ Raw and semi-processed materials command low prices pound for pound compared with finished goods. It took tons of timber, fish, and other food products to equal the value of furniture, glassware, ceramics and textiles that had to be imported from England and Scotland (Glasgow was an early industrial city and port.). Glassware was already seen as useful for more than just window glass. The rum industry was taking off in Massachusetts and the people wanted bottles for spirits–and glass tankards that didn’t affect the flavor of drink the way metal and wood could and did, and didn’t stain the way ceramics did. However, as in Virginia, the English proved lousy managers, and in Massachusetts, additionally, there was the involvement of religion throughout their society and a serious difference of opinions regarding material items and how much time and attention should be given to them and how many and what should be produced and used in people’s homes. The result was that over time the glassmaking industry moved into New York and ‘South Jersey’ and then into Pennsylvania, and from there, elsewhere into the Ohio River valleys, where it stayed, after most of what had been in Massachusetts disappeared.

and Quartz Crystal.

Note Hexagonal Quartz Crystal Shape

relates to Crystalized Silica Glaze structure.

The first glass was blown and then shaped by half molds for bases, or two part molds for some entire bottles, with additional shaping by use of paddles and tongs and clips. The first molds were made of hardwood but by the 18th century, cast iron was the usual mold material and a very small percentage were made of bronze. Molds had to be replaced frequently as the glass burned wood, and melted metals. Iron has a much lower melting temperature than glass. Though sodium oxide and other metal oxides and carbonates were added to glass to lower the melting temperature and to not let the silica crystallize as it naturally would do, the temperatures were still high enough to gradually ‘erode’ the designs and sizing from molds. Later, molds would be recut to resharpen the patterns when glass pressing machinery became used, but most early molds were simply entirely replaced. Silica, the dominant, basic material of glass melts at 4200 degrees Farenheit. Iron melts at 2800 degrees. If molds were to be made again in the U.S. today, I would hope they are made from one of the late 20th century steels alloyed with something like molybdenum or titanium to raise the melting temperature and make them more durable, requiring recutting or replacement less often.

Records of 17th and 18th century makers in the U.S. are scant, as most makers didn’t last, and fires and other disasters destroyed a lot of records. However by the 1750’s-1770’s, some were known and two groups were becoming dominant in the glassmaking industry. The names of a few of the makers tell you the ethnic identities of those who first became prominent and would lead the way in the development of glassmaking into a major U.S. industry by the mid-1880’s. In the 1750’s two ‘druggists’ in Philadelphia, John and Samuel Elliott were already making and selling ‘looking glasses,’ and decided to branch out further into glass making for a variety of uses including tableware. By 1773, they were regularly advertising for experienced glass blowers and cutters, persons who could use the copper engraving and cutting wheels and the grindstones to create glass ‘as fine as any from Bristol (England),.’ for their expanding ‘Philadelphia Glass Works.’ The Elliots promised good wages to skilled workers to attract and retain them. The Elliott’s were Scots. The other group, known for the ‘South Jersey’ tradition, began with Henry William Stiegel and the Stenger/Stanger brothers. Apparently Stiegl had some management issues also, more akin to the early English of the 1600’s, as an ad for a runaway worker named Stenger was placed by Stiegl. The British, including the Scots, had an apprentice and guild system in which apprentices were bound to guardians and guilds for a set period of time but as journeymen and masters had the freedom to move about and go where they were treated and rewarded best. In fact, as Augusta County, Virginia records, and Pennsylvania county records show, upon completion of an apprenticeship, the assigned guardian or guardians were required to provide the ‘graduate’ with one or two suits of new clothes including a cloak, a good set of tools, a bit of money, sometimes even a horse and saddle, and the former guardian-teachers were to help him find suitable employment for a first paid job, if the ‘graduates’ did not CHOOSE to keep working for their former master-teachers.

It appears from one ad that Stiegl ran, some Germans considered workers who had long ceased to be apprentices bound to them forever for the owners of the company to do with as they chose. The Stenger brothers had other ideas and soon became competitors to Stiegl. The British courts, including in their colonies, didn’t hold with skilled European workers being owned by employers, though African slaves were another matter, of course. Apprentices who ran away, though, were returned to masters. For one thing, they were usually minors. Boys were apprenticed about the age of 8 or 9 and had 7 to 10 year apprenticeships. The Stengers, however, by the time of the Stiegel ad had ceased to be mere apprentices.

Both the Philadelphia and ‘South Jersey’ businesses were expanding greatly by the time of the Revolution, fueled not only by coal from Pennsylvania but the increased anti-English sentiment regarding restrictions on manufacturing in the colonies, the quality of what was being sent to colonists by their own British cousins, the prices–and after the French and Indian War all the import taxes being then assessed–adding insult to injury.

Now people may wonder why did the Scots and Germans, and for that matter, the English, become involved in manufacturing, including glass manufacturing so early? Consider the economic life of the nations and the people of Europe at that time. Almost 90% of all economic activity was agrarian for families. You had to grow food and raise livestock to eat. There were markets in towns, of course, but what was there for food storage? Canning did not yet exist and neither did refrigeration and freezing. There were at best root and cold cellars for limited storage of some foods at 50 or 60 degrees in summer. Straw as insulation and heavy wood doors became used for ‘ice houses’ and ice could be brought that had been stored in larger facilities after being cut in winter. However, then you had to plan on getting rid of the water once the ice melted and not everything benefited from cold storage with high humidity. Otherwise, a lot of storage was done in barrels and ceramic pots and jars, with a lot of salt, alcohol, vinegar, or, in the case of fruit preserves in ceramic, a thick layer of wax or tallow from animal fat. Food production was also affected–and limited–by the amount of arable land and climate. It was greatly reduced in winter. If one looks at the latitude of most of Europe and remember that the world was much colder before the mid-1800’s, one can see and understand how most of Europe particularly, Germany, Scandinavia and Scotland had a real problem with 5 months or more of winter and rocky, glacial scoured land and a limited number of alluvial plains and valleys. Then two other things happened. The centuries of warfare between England and Scotland ceased with the Scottish royal family becoming kings of England, and the Protestants and Catholics, after a more than 30 years full civil war came to a kind of truce. The populations in Germany and Scotland expanded greatly, but the agrarian resources did not. Both, along with the Netherlands, Scandinavia and England had to find more occupations for their growing populations, and to trade for more food. They had to invent high quality manufactured goods and create markets and demand for them. They also had to find new products that not everyone else could produce as well or in as great quantities. Germany and parts of Scotland and England had a resource for glassmaking that not everyone else did: coal. Glassmaking, though it uses a lot of a common item, high silica sand, needs a high temperature to produce–nearly twice as high as what iron requires, and higher than even bronze. As an industry, glass making required a good fuel that could maintain consistent high temperatures and plenty of it. By just after 1000 CE England was already using coal again, rediscovering mines that the Romans had established. Cologne, in Germany which became a large glassmaking center for Germany was not far from the coal-rich area of the Saar. The Romans had also mined coal in the Rhineland and left their diggings.

There was something else that developed out of the Lutheran Germans and Presbyterian Scots, an interest in science and a willingness to put the discovery of and understanding of materials and the workings of the planet and universe before speculation based church dogma. The enlightenment and most of the sciences and high technologies were closely connected to the Scots and Germans by the late 17th century. Glass making is also a complex process involving chemistry, mineralogy, physics, thermodynamics, mathematics and engineering. A large part of our modern high technology hardware and equipment development has its roots, its foundation, in glass-making. For one example, those modern telescopes, the Hubble and Webb, we now have in space with their mirrors and lenses would not have been possible without the developments in glassmaking by the Germans and Scots, particularly as emigrants to what became the U.S. All of the scientific glassware, and the microscopes we now use for medicine, pharmaceuticals, creation of polymers and other new materials would not have existed without the industry and imagination of these early Scots and German Americans. The tableware and home decor graced millions of homes, and was a highly profitable industry for the U.S.–we were once the world leader in glass making–was the result of Scots, English, Irish, German and Central European American science and also a tribute to it., We, their American descendants, have destroyed a lot of the products and let the industries themselves go to Asia–turning out our own best legacies and spurning our own ancestors, and eroding and diminishing our own high technology future.

So this series intends to show bits of what we lost and something of the companies, the designers and makers, and products that for over 200 years were a key part of what made us great as a significantly ‘Celtic-American nation’ and inspire new respect and possibly some resurrection.

The next part in this series will cover the great revolution of processes and the invention of pressed glass, and expansion of the 19th century that led to this becoming one of the greatest of all U.S. industries and all the Scots and Irish emigrants who made it so. It starts in 1807, with the looming second conflict with our British ‘parents.’ The English navy was already impressing Americans as sailors and doing its best to prevent our trade with France. The English had not forgotten how those stubborn mostly Scots and Scots-Irish that comprised most of the Continental Congress and first American armies and Navy under Washington and Jones had run to France for assistance–and gotten it. The U.S. was not yet a great power, but we did have one power and used it. President Thomas Jefferson put an embargo on the importation of a number of British goods–including glassware–and then he and Congress not only encouraged, even urged, the development of new glassmaking companies and tools. The President and Congress also,found ways to help FUND them, what we might call ‘subsidies’ and loans, etc. today. It worked. In fact, the idea was so successful, that the British retaliated by doing what the Venetians had done long before. The British prohibited the emigration of glass-makers, including blowers, cutters/engravers and mould makers to the U.S., which, of course didn’t stop them, any more than it did some Venetians who were willing to accept rewards from English and Scots monarchs as early as Henry VII and James IV to go to England and Scotland. The 19th century success that came out of President Jefferson’s grand idea, is the next article. Interestingly, one high-quality glass company in the 19th century paid tribute to him and was named ‘Jefferson Glass.’ Thomas Jefferson’s mother was also of Scots descent, Jane Randolph, whose father had been born at Dungeness, Scotland.

For further reading, if you can find copies–they are rather rare–sources I have used include, American Glass by George S. and Helen McKearin (another couple of Scots) ‘with 2000 photographs and 1000 drawings by James L. McCreery‘ published in 1941 by Crown Publishers of New York (and even printed in the U.S.), and Portland Glass by Frank H. Swan, published in 1949 by Wallace-Homestead Co., Des Moines, IA. (Yep, same family, even the same general branch, as that of my late mother’s family–and she knew nothing about these good people.) You’ll see many more Scots and Irish names in Bold, throuoghout the next articles.

This is the second of an occasional series

In the early 19th century, the U.S. glass-making industry developed mainly with two American inventions that improved quality, cut time and effort, and lowered production costs:

1. The two-part, and later the three-part mold, eventually made of metal

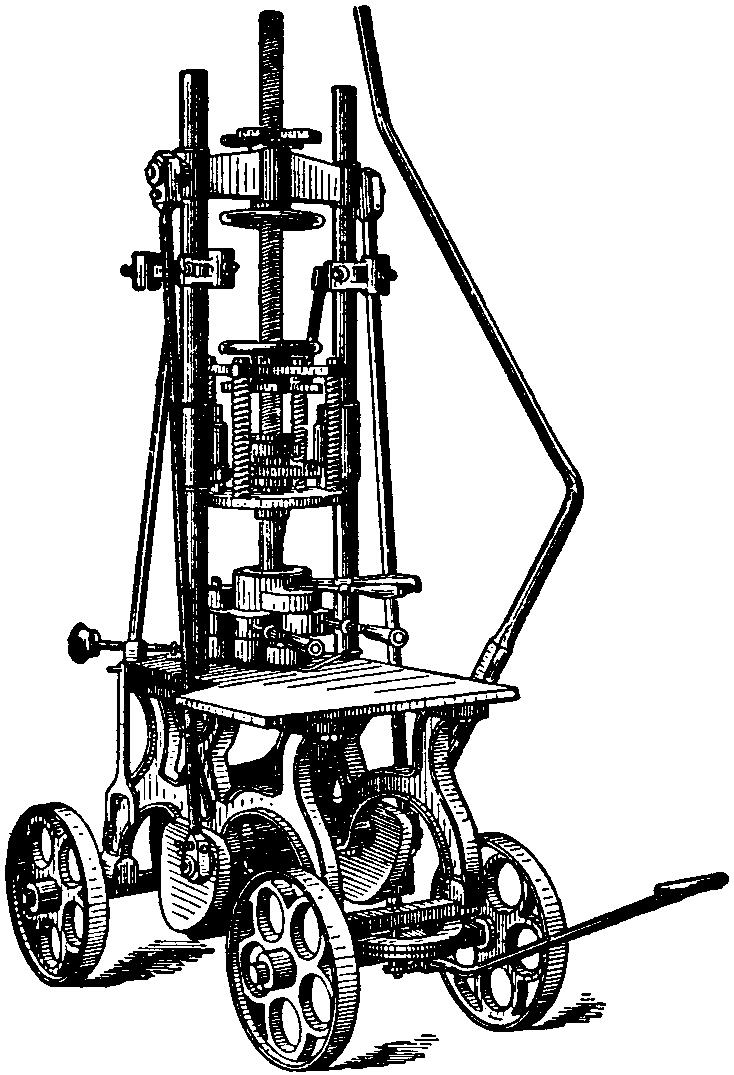

2. The ‘pressing machine’

Besides being more economical, the pressing machine greatly cut production time and enabled the makers to produce much more ornate pattern glass with greater consistency and quality from piece to piece in sets.

There would still be some engraving and cutting, but mostly to enhance the facets and cuts already produced by the mold. Thus, there would be a need for less time with copper wheels to have a result that resembled fine blown and cut crystal by the best Irish and English makers.

This prospect actually terrified the English makers and merchants and they took measures to slow or prevent the success of American competition. They still hadn’t forgiven the U.S. for rebelling successfully and leaving the empire and the U.S. hadn’t forgotten or forgiven them for their deeds before and during the War of 1812 including burning the Capitol.

Prior to the pressing machine and cast iron and bronze molds, glass was blown and then shaped by hand tools and raised decoration was often from additional pieces of blown glass then applied while hot to the base piece. It all had to be done quickly and care taken not to break the base. Quality was inconsistent, and symmetry of patterns and elements of patterns was hard to achieve. Talented,and experienced glass blowers and shapers were in short supply. England began restricting the immigration of skilled UK glass workers. That, of course didn’t entirely prevent glass makers from leaving, especially from Ireland, where the restriction was just one extra bit of insufferable oppression, but the restrictions and watchfulness of some company managers and owners did limit the emigration for some decades of the most skilled glass makers. Molds became an aid and substitute for the lack of glass blowers and shapers for the early U.S. companies.

The earliest molds were made from wood and were one piece or a hinged two piece and the pattern was only on the lower half or maybe two-thirds of a piece, the molten glass being blown into the mold. The initial patterns did not have high relief because the glass was only lightly pressed while being blown into the molds. Additionally, wood being able to burn at 450 degrees fahrenheit had to be replaced frequently.The molds charred and marred the glass, even though they were watered before each use. Some improvement was achieved by aging select, very hard and dense wood for some years first before using it to carve the molds, but that slowed mold production, and as demand for glassware increased, so did the need for this expensive aged select wood. Imagine the amount of wood needed if every third or fourth use of the wood mold resulted in destruction of the mold by charring or cracking. Imagine the time then being spent carving each and every new mold by hand. Damage to molds only increased and accelerated with the invention of the, high relief, three part molds had been first developed in the New England Glass Company at Sandwich, Massachusetts by about 1815, and that allowed the pattern to be on both the inside and outside of glass pieces. It was clear by the 1830’s something better had to be made more quickly and with less cost to keep up with the pace of growing demand for glass tableware and decor. Skilled mold carvers were also in demand and in short supply. Initially, one mold maker of note, Enoch Robinson, a carpenter at the New England Glass Company in Massachusetts, made wood molds for both the Massachusetts and Pittsburgh companies.

The difficulties with wood and the long aging time required, caused the companies to begin experimenting with other materials. This quickly became imperative when the Bakewel family perfected and patented their glass blowing-and-pressing machine in 1834. John P. Bakewell had developed the first machine in 1825, but continued to improve upon it for several more years before patenting two designs for a glass press in 1829 and his later glass blowing machine. When pressure was added to hot molten glass to obtain more detailed results, the wood molds, which already had been charring, began charring even more, and also cracking.

To limit the charring and cracking, next molds switched to brass and bronze, both of which were very expensive. An attempt to cut costs by having a brass lining of an iron mold usually ended in disaster when the disparate metals came apart from each other and melted at different temperatures next to the much hotter glass. It was in the 1860’s that cast iron molds finally became the norm, largely solving these problems, and the pressed glass industry expanded as never before. Still cast iron had a lower melting temperature than glass, but it did not burn or char like wood. Instead, the patterns were ‘diminished’ and blurred by slight amounts of melting of the molds but with iron, these details could be recut several times. After so many uses, the molds had to be melted down again and remade entirely. This would continue to be a problem for the industry until most U.S. companies were put out of business in the 1970’s, and 1980’s. The owners of the companies never invested in new mold materials using the higher temperature tolerant alloys being developed for the military and space industries.

The first real multi-person glass company, and oldest long running glassware company in the U.S. was established in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania by Benjamin Bakewell and Benjamin Page, in 1808 and later became better known as the Bakewell, Pears and Co., after a change in principal partners. It was not the first glass company of note in Pittsburgh but outlasted its initial competitor. The first well recorded company who initially competed with Bakewell and company was actually O’Hara Glass, founded in 1797 by James O’Hara–and a single proprietorship. However, Bakewell and company concentrated on fine tableware and decor at the same time the middle class and families were both growing and with peace after the War of 1812 and the Indian wars of the Ohio valley, a taste for greater comfort and luxury was also developing. Bakewell also prioritized improvements in molds and shaping glass to have greater quality and cost efficiency. The first ‘flint glass’ (leaded glass) chandelier made in the U.S. was made by Benjamin Bakewell and company in 1810 and was noted in early gazetteers as ‘something to be seen when visiting Pittsburgh.’ Until 1819, this company was the only one in the U.S. producing fine cut and engraved tableware. By 1825, the company had been awarded a ‘reward for the best cut glass- pair of decanters by the Franklin Institute of Philadelphia’ in its annual exhibition. Sons, Thomas and John Bakewell patented the first successful glass blowing and pressing machine in 1834. John Bakewell had earlier patents, including a ‘press’ in 1829. Unfortunately, the U.S. patent office had a fire in 1836 and few original records and drawings of the patents prior to the end of 1836 remain. The company lasted until 1882. Skilled employees and managers went on to help develop new companies in the Ohio River Valley states, building upon the foundations established by the Bakewell family and its partners. Although a number of fine pieces of their work still exist in homes and museums, not many records of the company do. In 1845, a fire destroyed part of the plant and many records. In 1882 when the company closed, the remaining records were mostly thrown out by those who had acquired the remains..

Interestingly, the next improvement, the cast iron molds, which became the industry norm, developed along with better guns, particularly cannons, and tools for working the interiors of the molds better and faster. The Mexican American War and the Civil War benefited the iron and steel industries by requiring better and more consistent weapons and detailed work in and on those. In 1866, Michael Sweeney, of Wheeling, West Virginia had patented a new chilled iron mold that worked well for glass. By 1870, nearly all the glassmakers, eager to resume selling to all Americans now that peace had resumed, had begun using cast iron molds. With the end of the U.S. Civil War, the mold makers who had been making molds for weapons were happy to have new business.

The first major, long existing competitor to Bakewell, Page and company, later Bakewell, Pears and company, was founded in Boston, Massachusetts as the ‘New England Glass Company’ by Amos Binney, Edmund Munroe (spelled Monroe in most records), Daniel Hastings, Demming Jarvis (Deming Jarves in most records) and associates. The founders made a concerted effort to attract skilled glass cutters from abroad, particularly the UK and Germany. The company built 24 cutting mills powered by steam and had a six pot furnace with a capacity of 700 pounds of molten glass per pot. It also built its own red lead furnace for the metal that added to New England glass gave it strength and brilliance. Despite all the technology, management was sometimes an issue and people left this company to found their own. John L. Hobbs would eventually leave to found Hobbs, Brockunier & Company which would eventually employ Harry Northwood and his Dugan cousins for a time.

Deming Jarves, descended from a French Huguenot who had initially settled on the Isle of Jersey, had been made the general manager of New England Glass Company but did not feel he was given enough freedom to exercise his judgment and severed ties with the company in 1825 founding the Boston and Sandwich Glass Company, which is where the name Sandwich Glass describing a particular style of New England glass developed in the first half of the 19th century originated. Sandwich Glass came to be associated with a lacy style of decoration in multitudinous patterns, usually with a stippled background. The stippled background and affordability of increasingly intricate patterns was made possible by the new molds and the skilled artisans who carved them. Despite the loss of Jarves, who became a significant competitor, New England Glass Company continued to attract top talent and then see it leave. Jarves took some of those disgruntled employees and then lured an English glass maker to the U.S. to begin training more, paying him a then princely sum of $5,000 for his services. Jarves also brought in large numbers of Irish glass workers, in addition to those from continental Europe and England. Jarves introduced the first opalescent and ruby or cranberry glass to the American industry. He was among the first to employ metals experts and chemists for his increasingly diverse wares.

About 100 years after the first ‘lacy Sandwich glass’ was made, the style was somewhat resurrected in later companies’ patterns named ‘Sandwich’ such as sets made by Duncan Miller, Indiana Glass and Anchor Hocking. Westmoreland also had ‘Sandwich style’ which, to be differentiated from the competitors, was named ‘Princess Feather.’ The best of these retro styles were probably Duncan Miller’s ‘Sandwich,’ and ‘Princess Feather’ by Westmoreland.

In 1826, the Boston and Sandwich Glass Company succeeded in persuading Thomas H. Leighton, a skilled gaffer and more in England to defy the English restrictions on glassmakers emigrating to the U.S. and made him superintendent of glassmaking for New England Glass. Leighton fled England with his entire family, including sons who were also becoming very skilled. Leighton, like the Northwood’s and Dugan’s, had been raised in the famed Stourbridge area of England that produced many of England’s best glass makers and glass artists for over a century. Thomas Leighton stayed with New England Glass until his death in 1849 and was succeeded in the position of superintendent by his son John. However, another son, William Leighton ‘who was skilled in every branch of the business, and especially so in the matter of making the metal and colors,’ left in 1864 and joined the J. H. Hobbs, Brockunier & Company in Wheeling, West Virginia.. He had discovered an original formula for making ruby glass and would take that knowledge with him. Yet, a grandson of Thomas, Henry Leighton continued on at the company and became one of the most expert engravers for New England glass. Eventually, Leighton would leave Hobbs and Brockunier and with Scots descended brothers, W.A.B, Andrew and James Dalzell of Pittsburgh and their banker friend of Scots-Irish descent, Edmund Gilmore would found a highly regarded company named Dalzell, Gilmore and Leighton, at Wellsburg, West Virginia, in 1882 with a 2 acre factory built in 1883.

Again, this is where economics caused another turn in the industry. Wheeling and nearby areas like Wellsburg became popular for new manufacturing because the railroads that networked the large eastern cities had finally reached Wheeling in the 1870’s, and made transportation of goods and raw materials faster and less costly. What wasn’t transported by rail, could easily go up and down the Ohio and Mississippi River to and from many large cities and towns–good markets as well as sources of materials. The Ohio River area and western Pennsylvania became home to dozens of glass makers from the mid-19th to mid-20th centuries.

West Virginia, like Pennsylvania also had coal, and a new resource just becoming developed, natural gas. Natural gas was less costly and the piping, etc. took up less space than coal. It produced more even heat, and light for the plants. It also was cleaner and healthier for the workers, even though they were also still using lead in some of their wares. Hobbs and Brockunier with Leighton’s help had developed a newer high quality ‘lime’ or ‘soda’ glass that while not always quite as brilliant or heavy as ‘flint’ (leaded) glass, was also less costly to produce. Bryce Higbee would later improve upon this glass and make it dazzle. Bryce was another Scots-descended entrepreneur in the glass industry who did very well. Dalzell, Gilmore and Leighton also had a second rented building in Brilliant, Ohio and Ohio was taking notice of the lucrative industry Pennsylvania had long enjoyed and which was making its way into West Virginia.

Ohio had all the raw materials, including fine sand in several areas of the state and wanted in on the action. The town of Findlay, Ohio, in Hancock County, and not far from the growing affluent industrial cities of Toledo, Detroit and Cleveland, claimed to have abundant supplies of natural gas–more than Wheeling and Wellsburg, West Virginia and offered land for building and 5 years of natural gas at no cost for glassmakers to relocate there. By 1889, 16 glass making companies had set up business there, including Dalzell, Gilmore and Leighton. In 1891, however, during a hard winter, the town cut off supplies to the companies, most of whom then left within about two years. Dalzell stayed on until 1899 when it became part of the syndicate called ‘National Glass.’ Eventually, some of the Dalzell family returned to West Virginia, to New Martinsville Glass and also founded Dalzell Viking. These two companies then merged in 1972 and as Viking glass went on for over another decade. This made the combined enterprises of the Dalzell family one of the longest running glass making business in the U.S. having lasted over 100 years.

Meanwhile, in the 1880’s the New England Glass company was having problems with fuel costs and availability and striking workers wanting more pay, and the principal owners had not learned much since Jarves and Hobbs left. Members of the Libbey family became involved with the company. The Libby/Libbey family was in what became Maine between 1635 and 1650. There is debate over the origins of the family and surname. Some sites point to a family seat having been in Yorkshire and that would fit the names of the villages and towns in Maine where the family surname was found earliest: Scarborough and Berwick. However, family history researchers in the early 20th century from Maine and Massachusetts believed the family was originally from either Cornwall or Devonshire. The surname is additionally odd in that it is from a female ancestor, not male. That also indicates the possibility of very early Celtic origins either along the Scots border with England or Cornwall where Celtic matrilineal inheritance lingered. It’s believed to be Norman-Celt, a diminutive of the French name Isobel, ‘Libby.’ Either way, the family was at least partly ‘Celtic,’ in its origins in the UK, and by the time Libbey Glass was establishing itself in Ohio, the family had a number of marriages to persons of definite Scottish descent. In 1872, William L. Libbey had become ‘agent’ (General Manager) of the company and his son, Edward Drummond Libbey was also employed there by 1874. They had already become sole owners of the Mount Washington Glass works of South Boston, founded by Deming Jarves for his son, George who had not done well with the company. The Libbey’s had already become sole owners of the Jarves’ company by 1866, and had moved the Mount Washington company to New Bedford, Massachusetts in 1869 and then sold this company to the Pairpoint Manufacturing Company. The Mount Washington and Pairpoint companies became known for high quality, expensive, decorative art glass, which could have dramatic ups and downs depending upon the national and regional economy and the finances of the elites. All luxury goods companies are risky business ventures with inconsistent income. The Libbey’s decided on a different direction that had wider appeal and a company that provided much more. A certain amount of diversity of goods often helps companies to survive long-term better. Perhaps the practical Scots genes helped determine the choices the Libbey family made and ultimately ensured its success. The Libbey’s then moved what was left of the declining and fractious New England Glass company to Ohio, and rebuilt and expanded its operations into several divisions over time: Libbey Glass, Libbey-Owens-Corning (the last connected to ‘Corningware,’ ultimately), and Libbey-Owens Ford.

Lest one think that they were totally against the New England workers, it is clear from some records and history of the company the Libbey’s transferred a number of skilled workers from Massachusetts to Ohio and paid them well in Ohio, which at that time, also had a lower cost of living than Massachusetts, besides having more resources than Massachusetts. Many central and east Europeans later found excellent employment and pay, well enough to buy homes and furnish them well, from the end of the 19th century and all through the 20th century. Findlay, Ohio may have mismanaged their natural gas, but other areas of Ohio did not. By the late 20th century, Libbey was a huge conglomerate that made plate glass, later automobile glass, scientific glass, and of course, kitchenware, and continued the New England Glass tradition of producing fine, but different table ware and fine decor. Libbey’s tableware and decor glass included both blown and cut in the traditional high quality crystal styles, and the less expensive pressed–addressing multiple markets. The Libbey companies still exist. The Ohio rebuild and expansion was led by Edward Drummond Libbey.

For further reading a few of my sources were: American Glass by George and Helen McKearin, 1941, Crown Publishers, New York, and A Fifth Pitcher Book, by Minnie Watson Kamm, 1948, 2nd edition in 1956, privately published and rights owned by Kamm family, section: ‘Notes’ (on various glass companies), ‘Boston and Sandwich Glass Company’ pp 158-161; ‘Dalzell Glass Company’ article by https://brookecountywvgenealogy.org/industrial2.html.

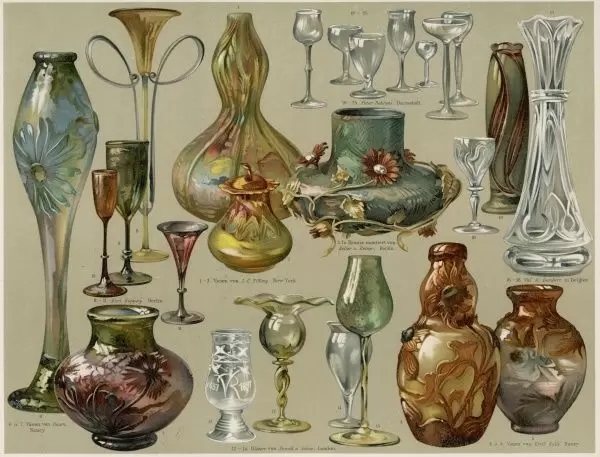

Next article: Part 3: Brilliance and Fizzle. This will cover the ‘gilded age,’ influences of Art Nouveau and Art Deco, the Great Depression and the Post World War II decades.

This is the third of an occasional series. This will cover the ‘gilded age,’ influences of Art Nouveau and Art Deco, the Great Depression and the Post World War II decades.