Celtic Women

|

AmeriCeltic provides accurate information on Celtic Culture and History. |

Support our work! |

Click Here to subscribe to our weekly Email Newsletter, and get updates every Friday. |

Table of Contents

Women’s Civil Rights in Celtic Societies by Cecilia Fábos-Becker

Equal rights for women in ancient Ireland by Ali Isaac @IrishCentral

By blood we are mostly a Celtic nation, with a long, rich history of Celtic culture in attitude and law regarding human and civil rights. If more people knew what that history was, they’d be appalled at the attitudes, behaviors, deals and stated goals of most of candidates for high elected office in the U.S., particularly as they regard women, the elderly, the truly skilled and educated, and living children. This article reviews the status and rights of Celtic women, a somewhat sensitive subject, but real Celts will appreciate it as part of their cultural heritage.’Bay Area author, Catherine Duggan, recently published a book, The Lost Laws of Ireland (2013, Glasnevin Publishing, Dublin, Ireland).

This book reveals the status, rights and obligations of Celtic women as described in Brehon and other pre-Roman and pre-English law. There are additional references to pre-Roman and pre-English laws in a number of Scottish history books and commentaries by the Romans and English about the Scots, particularly between the 3rd and 10th centuries.’The difference in status of women is startling. Compared to Brehon law and the Christian Church of Saint Patrick, Aidan and Columba, the Romanized Christian Church and related laws and cultures considered women mere property. It did not matter what was the status of their parents, what their parents contributed to the marriage, nor their education and skills. They could not own property, could not own labor, livestock, nor pass on anything to their children by choice. This was very different in Celtic societies.’Under Brehon law, women were ordered to be protected by their fathers, husbands and sons. If injured or killed they had an ‘honor price’ based on rank at birth and their own education, skills and integrity. If a woman married a man of equal rank, she continued to own property in her own right after marriage, and could buy and sell property, have separate as well as common earnings. According to her will, upon a woman’s death she could could dispose of property inherited from her own family back to her own family under the care of the ranking male. Property acquired in a woman’s own right, before or after marriage, could be disposed of by her choice and will to whichever sons and daughters she preferred. Primogeniture among males was not the sole rule of inheritance.

Marriage was governed by contract sections of law and also laws against extreme violence. Women could divorce men for violations of the marriage contracts, infidelity, slander and abuse, especially if any physical abuse left a blemish. Polygamy was also legal but the second wife had only half the status and honor price of the first, though her sons might be considered equal for a father’s inheritance, since a father did not have to give everything to his first born son. A man could divorce a wife for having an abortion or for smothering or otherwise killing a child.

Brehon law continued to operate in Ireland until the 1600’s and in Scotland a similar form of law continued until the beginning of the Stuart kings. In fact, according to Patterson’s History of Ayrshire, widows had property rights and other rights up to the time of the Act of Union and later, at least until 1745, and a woman could demand and obtain a divorce. When the Presbyterian Church was formed in the 16th century, councils of elders were quickly agreed upon by the church communities to be elected by both men and women and both men and women could be elders, and religious teachers up to a point.

Scotland was at one time a matriarchy. Its Pictish kingdom was often ruled by a Queen in her own right. Over time, males were crowned, but becoming a king was determined by the mother’s family, that is who your mother was, not the father’s family. Even the Stuart kings ultimately came to the Scottish throne on the basis of the marriage of a daughter of the preceding king who had no sons. Civil strife sometimes occurred because there was no guaranteed preference of birth order among daughters, and outside mercenaries or mediators could be and were brought in by one husband of a daughter or another. This is how the Plantagenet kings of England began making inroads into Scotland began outright invasions at times into both Scotland and Ireland. It was, ideally, a combination of the marriage of a daughter and the honor price–the worth–of her husband that determined the support for the kingship of one husband of a daughter over another. Outsiders were supposed to be left out of the decision. In both Ireland and Scotland, leaders of families or clans was a combination of heredity and election, and likewise kings. However, disagreements could and did lead to violent conflict so it often was a combination of force of arms, as well as wealth, intelligence, and the degree of non-violent popular support that led to a clan or family chief being decided or a king. This was both a strength and weakness of the nations. Enemies could and did profit during civil strife over leaders at the lower and higher levels, especially when someone whose ego outweighed his sense of community invited them into the fray.

Women were also accomplished queens and warriors in their own right in pre-Romanized society. In the 60 CE the Romans battled Boudica (Boadiccea), Queen in her own right of the British Iceni tribe who led an army of 100,000 against the occupying forces of the Roman Empire in the then Roman province of Britannia. In the 16th century, Queen Elizabeth contended and negotiated with Grania O’Malley, who ruled the provice of Connaught in Ireland, where the Brehon law of the native Celts still ruled.

By 1654, the English had finally completed the conquest of Ireland and their oppression began in earnest. These conquerors outlawed the ancient Brehon laws, imposed their English laws (see Penal Laws and Highland Clearances). Within a generation, Celts began emigrating to the North American colonies, and after serveral failed revolts, by 1750 over 1,000,000 Scottish and Irish emigrants had populated the American colonies, especially along the Appalachian Piedmont, where English law did not reach. Scottish and Irish famines of 1837 and 1847 added at least another 1,000,000 Scottish and Irish emigrants to America.

Though these more egalitarian laws and rights were in decline in Scotland and nearly wiped out in Ireland, the memory, and oral and written histories of what once was, continued for a time in the U.S.. The memory was refreshed by a huge new immigration of Scots and Irish who had continued to suffer under the English in the famines and Highland Clearances, and had kept the memory alive the stories of the old ways. In all these cases, the influence and greater control of the exclusively male, feudal, classist society of England was seen as a major cause of loss of rights of women, increased poverty of women and children, as Dickens and Austen described, and one more reason for emigration to America where a new society might be created and some treasured older values revived.

Unfortunately, the lingering influence of the English usurping Brehon Law lasted for centuries. It wasn’t until the mid to late 19th century that American women finally regained most of the civil-rights that they had 400 to 800 years earlier in Ireland and Scotland.

The battle for womens and human rights continues today, as too many ignorant men still cling to Romanized and pre-modern English traditions. Some still regard as women as little more than “senseless property” and and try to impose these more restricting attitudes, as law, upon a mostly Celtic nation. Like the Romans, they all too willing to use brute force when persuasion by their eloquence fails to convince their victims, and we still have a long way to go to restore justice for the still too prevalent oppression. Real full equality of women, as once existed in pre-Roman times, may still depend upon women being willing to do battle for their equality and rights as Celtic warrior women of yore once were willing and able to do.

@IrishCentral, March 27th, 2023

Queen Medb of Connacht is arguably the most famous female character in Irish mythology. Her story is told in the Cattle Raid of Cooley, or Táin Bó Cúailnge in Irish.

In it, she competes with her husband, Aillil, over which of them possesses the greatest wealth, and demands the use of Donn Cúailnge, the big brown bull belonging to neighboring King Dáire mac Fiachna. When he refuses, she has no hesitation in leading her armies into battle to get it.

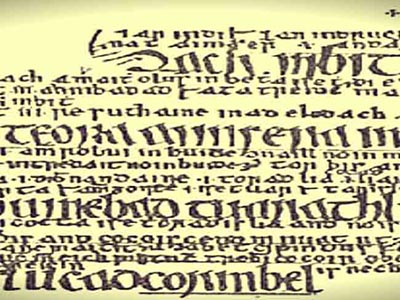

The very fact that this story has survived culling at the hands of the Christian monks, who fixed the old oral tales in ink on parchment, is a testament to how highly she was regarded by the Irish people. She did not escape unscathed, however; the story focuses not so much on her good deeds, but the perceived weaknesses of womanhood; she is depicted as headstrong, ambitious, promiscuous, greedy, jealous, and vengeful, everything a good Christian woman should not be.

We may never know how accurate this portrayal of Medb is, but it does indicate that in ancient Ireland, not only could women be Queens, but they could lead armies, be warriors and druids, possess wealth and property in their own right, and engage in marriage on an equal footing with their husbands.