Researching Virginia and West Virginia History and Records

By Cecilia Fábos-Becker – Published 2019-10-04

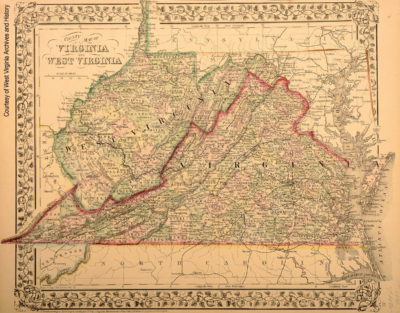

Things are always changing in family history research and many Americans have ancestors who were in Virginia and West Virginia prior to the American Revolution, and until 1863 Virginia certainly included what became West Virginia. In 1755, they were one, and one of the most populous colonies with a population of 85,000 men, women and children, excluding slaves, but including indentured servants. By 1775, about one generation later, many considered it the most populous of the thirteen colonies.

At this time, Virginia also included what became, Kentucky, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois–aka ‘the Northwest Territory” though this was to some extent disputed by Pennsylvania. Tens of millions of Americans have one or more lines of ancestors that for a generation or more lived in Virginia and West Virginia. It also was a state that had a great impact on several key events in late colonial history, Revolutionary War history and the founding of the nation and many important people who were well acquainted with neighboring families. Many people had ancestors who personally knew George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Patrick Henry, James Madison, and others. Some ancestors even had transactions or interactions, or served under these famous people. Virginia and West Virginia are states, then, of keen interest to both family history and general history researchers and writers.

For many years, I’d looked at my generally trusty County Courthouse Book by Elizabeth Petty Bentley, and as they were created, county websites, state library/archives, etc. websites and like, I’m sure, many others, kept seeing “burnt counties,” particularly for one group of counties, with the short, often one or two line descriptions of courthouse fires, flooding, etc., and one incident in particular. In about 1864, a group of counties, as the Union army gained the upper hand in the Civil War, had become concerned about saving their records and put them into wagons to take them all to a ‘safer’ location for the duration of the war. It was already seen in other states that the understanding of the need for records in the future was not universal among Union officers, much less the men beneath them and courthouses and their contents were being shelled and/or burned. The North was effectively making war not only on the current South, but its ancestors as well. We call that cultural genocide, today. It was standard for warfare, then. That lack of understanding and foresight eventually would have major consequences on chains of conveyance for real estate, taxes and war reparations demanded by the Union of the southern states, but few were thinking about what would be needed after the war. In this incident, in one or two places, a group of wagons were attacked by Union army units, unexpectedly. One was stated to be “near Petersburg”, Virginia, and definitely included county records from at least six counties. In most accounts, the wagons and their contents were burned. However, I recently found a number of articles in the quarterly magazines of the annual volumes of the “Magazine for Virginia History and Biography” that show this was not entirely what happened. Some contents of some of the wagons were partly burned, but not all the records. What mostly happened was Union army soldiers took many volumes of records of the several counties as “booty” or “souvenirs,” and some volumes by 1894 were already making their way back to Virginia, to counties or the State Library/archives as children and grandchildren of the soldiers realized what those old books and papers in father’s/grandfather’s old war trunks were and that they might still be of value.

During and after the Centennial of the U.S., 1876, family history became a serious hobby and some people realized that records of what happened to individuals were an important part of that. Also, the country was generally becoming more prosperous and buying and selling more real estate, however large or small the parcel. The courts were establishing that chain of conveyance was important to determining not only ownership and who had the right to sell property, but also who has the right to collect mortgage and rent money. By this time, it had also been seen and realized just how much legal and financial chaos had occurred in southern and border states from missing volumes of deeds and tax records. It affected the abilities of the southern states to collect taxes–including those expected to be used to repay the Union for the cost of the war.

There are partial sets of records, now, for many counties still being described as ‘burnt counties” with “almost nothing left,” but according to the people who found these, most are NOT in the counties, but ended up in the state library and archives and sometimes universities and waited for curious researchers to find them and transcribe and print them, in magazines like the “Virginia Magazine of History and Biography.” I found records from SEVERAL counties in the series of magazines for just this one magazine. There are at least three historical magazines which printed articles containing these records, personal papers of notable people, etc. that had also been originally taken during the Civil War and more. I also found that a large body of the original papers of Thomas Jefferson, including correspondence is not at Monticello. When he died, his estate went bankrupt and his heirs donated or sold off many of his materials. The College of William and Mary has a large collection of his writings and published copies of many in the “College of William and Mary Quarterly.” Others ended up at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, and some in the local Albemarle County Historical Society. These materials included many mentions of many other individuals and families who Thomas Jefferson knew and with whom he interacted, did transactions, such as trading fig trees brought from France for a wagon-load of clover seed (“to improve his pastures”) that he did with a member of one of my late mother’s ancestral lines, and with whom he exchanged his thoughts about many issues. George Washington’s materials, and those of James Madison (the “father of the Constitution”) ended up similarly scattered. It was not an idle comment that these men and other leaders literally gave their fortunes and sacred honor to fight for the independence of our nation and establish it as a viable, nation with a real, new government. Wars cost money, building libraries and other public buildings also, running a government, ditto. The U.S. had no real system of taxation initially. A lot of private money was used instead, provided by those who cared most, and spent years of time, effort and money to give us what we have today.

So when you are researching your families who lived in or passed through Virginia and West Virginia, don’t assume that burnt counties mean everything was burnt, and find and look through these old magazine series, the “Virginia Magazine of History and Biography” published from 1894-1965; “Tyler’s Quarterly Historical and Genealogical Magazine” published from 1919-1952 and the “College of William and Mary Quarterly” which has been published for at least 150 years and is still being published. You’ll be surprised at what you find.

As to finding them, that can be a little problematic. There are few libraries which have the entirety of all three collections and none are entirely online, much less free. Of course the Library of Congress has all of them. Most, if not all, of the volumes of the three are also at the main LDS library in Salt Lake City, and quite a large part of all three are at the University of Wisconsin Library in Madison, along with the famed and priceless Lyman Draper Collection of historical records of the late colonial, Revolutionary and early U.S. nation periods for Pennsylvania, Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, and North Carolina. Parts of the series of the three magazines are at other college libraries. You have to inquire of the libraries as to how much of the series they have. “WorldCat.” does not always indicate how much of the series is where, just that libraries have the magazine collection, not whether or not it is a complete collection. Not all libraries have digitized their entire card collection to show what materials that are not online are in the library, also.

The “College of William and Mary Quarterly” probably has the fewest complete issues online, though some issues and many articles are. However, I did find the table of contents for nearly all issues online, and a librarian was willing to check the indices for the magazines, which were in an in-house computer, for specific individuals and incidents across a certain time frame, which was very helpful. Among all of this I was able to determine that a particular article describing one incident involving certain individuals had NOT been published in that magazine which helped me move on to searching other sources more rapidly. Librarians are often far more helpful than many people imagine. They also get bored silly with the same old requests from students for assistance in finding resources for the same old popular topics long used by professors and students. The librarians like the occasional new and different request, and some welcome a challenge.

I found that a combination of four sites had the annual volumes of 1894-1924 of the “Virginia Magazine of History and Biography” online and free and likewise several early years of “Tyler’s Quarterly.” After sometime in the 1920’s however, “free” may not be really free.” HATHITRUST has both some early years of the magazines and one can use keywords and names relatively easily with the CONTROL “Find” keys to whip through the magazines in particular searches. JSTOR is a site that has digitized many more years of the magazines, but divided the years into the “quarterly” magazines, and then each quarterly magazine into the individual articles–and no index, and harder to use “search” techniques. I’d love to see all the magazines available through HATHITRUST. Unfortunately, that’s not so yet. You can register for free with JSTOR and have truly free access (downloads) for 6 articles per month. God help you if you can’t figure out if an article is truly useful or not from just the title of the article. After six articles, not magazines, but just articles within the magazines, you have to have a PAID subscription and the more you pay, of course, the more articles you can download. It also helps to have a lot of computer memory. You can’t just read the articles online for years after 1924. What is “free,” for the collection after 1924, are short one and two paragraph previews of the article, usually the first paragraph or two, which may not get into the meat and most important content of the article. I found it ironic that you can get access to census records up to 1940, but not access to old, no-longer published magazines past 1924. It seems the Federal government, in this situation at least, is more liberal and generous than some universities and internet entities.

Last, the websites and usual basic “how to” books on family history research are not always up to date on what is available at county courthouses, libraries and state archives–and how much is online or not. I had a recent experience trying to find some county records in West Virginia. Most of the older records of many counties were sent away from the courthouses, and another researcher and I discovered that current clerical staff did NOT know where the records had been sent, when and by whom and how many of what type went where. Even the higher ranking “deputy clerks” of the courthouses did not know that their own records had been transferred to the state archives and several types were now available for searching online. Additionally, I found non-county websites that even stated some older records had been sent not to the West Virginia archives, but to the Virginia archives. Most of the counties civil birth marriage and death registers were sent to the West Virginia state archives. However, the wills were not, and neither were deeds and civil suits. I found that older will records in several counties had been moved, but were also not in courthouse archives, and were not in the state achives, either. No one currently employed by the counties knew were some types of older records were, any longer.

I also found that libraries in this state were not always terribly responsive, though it’s likely some types of older records are there, in “history rooms,” or sections. Historical and genealogical societies were even less responsive. For researching West Virginia prior to about 1900, if records are not at the state archives, I recommend employing an experienced, local researcher who has had enough years of experience to know where the older records that are NOT in the state archives actually are, whether they are in courthouse archives in a different building from the courthouse, or in the basement of said courthouse, or in the main county library in the “history room” or in the nearest University/college library, etc.

Thanks for the info. I have been researching branches of my family for many years. Now I know why I cannot find more complete information on my ancestors from this area. Your knowledge of genealogy is vast and much appreciated. Thanks.